The State of Competency-Based Education in African Higher Education and Reflections for Action

Keba Hulela, Botswana University of Agriculture and Natural Resources, Botswana

Might Kojo Abreh, University of Cape Coast, Cape Coast, Ghana

Miriam Ogah, University of Education, Winneba, Ghana

Could it be argued that universities across Africa are at a critical juncture? The traditional model of higher education is facing unprecedented scrutiny from all sides, particularly from society, mainly made up of the general public and employers. There is a palpable crisis of perceived quality, with a growing number of university graduates being seen as lacking the requisite skill set necessary for the demands of the modern workforce. Concurrently, students are questioning the very value of a university degree, burdened by its high cost and the potential for significant debt when it does not make them the best, they ought to be addressing the ever-complex demands of the clientele of products of public universities. This systemic challenge necessitates a fundamental re-evaluation of our educational philosophy and practices within the framework, addressing the needs of university students and graduates with the requisite resources to make them functionally competent, leading to the touting of Competency-Based Education (CBE) as one of the alternative variants of training that can address the foregoing concern.

Competency-Based Education (CBE) has emerged as a powerful, transformative model capable of addressing the skills deficit gap that university students and graduates seem to be facing in Africa. Unlike traditional systems that measure success by time spent in a classroom and learning places, CBE measures learning itself. Students advance by demonstrating they have mastered the knowledge and skills required for their chosen field, regardless of how long it takes them to acquire them. Such required skills are not a luxury or aesthetic addition to their learning and training, but the core of the competencies they need to succeed. This paradigm shift promises a host of benefits, including improved quality and consistency, reduced costs, and a more accurate measure of student learning. A clear competency framework sends a transparent message to the outside world about what a university degree-holder truly knows and can do.

While comprehensive, continent-wide statistics on the adoption of CBE in African universities are still emerging, a growing number of nations are making significant strides in integrating competency-based and learner-centred approaches into their higher education systems. This shift is primarily driven by the need to produce graduates who are better equipped for the demands of the 21st-century workforce.

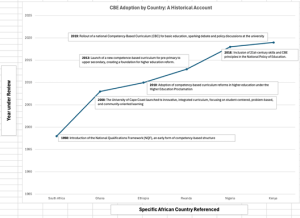

Countries such as Rwanda, South Africa, Nigeria, Tanzania, Zambia, and Ghana have been at the forefront of this educational reform. For instance, South Africa began its journey with CBE as early as 1998, aiming to produce a more skilled and employable graduate population. Nigeria has also made provisions for CBE in its National Policy of Education, with a focus on teacher training and retraining to build 21st-century skills. Similarly, countries like Kenya are implementing competency-based curricula at the foundational levels of education, which is expected to influence higher education in the coming years.

A study by UNESCO on the competency-based approach in Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET) in Benin, Ethiopia, Ghana, Morocco, Rwanda, Senegal, and South Africa has highlighted both good practices and challenges in implementing this approach. While these findings are specific to TVET, they offer valuable insights for the broader higher education sector.

Figure 1: Adoption of CBE in selected African Nations

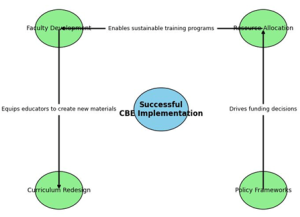

Despite this progress, the implementation of CBE is not without its challenges. Common hurdles across the continent include a lack of adequate resources, the need for extensive professional development for faculty, and the absence of robust policy and technical frameworks to support the transition from traditional to competency-based models. A survey of in-service secondary school teachers across three African countries revealed that while there is a positive perception of CBE, a lack of professional training and support affects the quality of teaching and assessment practices. Figure 2 offers a summary of the issues noted.

Figure 2: Interconnected Challenges in CBE Implementation in Africa

The promise of CBE is immense, but its implementation is not a simple task. It is a “wicked problem,” a term used by urban planners to describe issues that cannot be definitively resolved because they are complex, contradictory, and constantly changing. Wicked problems, like poverty or environmental degradation, have no correct answer; their solutions are “better or worse” and often involve a continuous process of adaptation and feedback. This framing is vital to our discussion because it underscores the reality that a simple, one-size-fits-all curriculum change will not be enough to implement CBE across Africa successfully.

The “wickedness” of CBE in the African context manifests in several ways. Firstly, the very concept of “competency” is challenging to define and measure. Stakeholders, including academics, policymakers, employers, and students, often have different versions of what the problem is and what a successful graduate looks like. The requirements of the workplace and of academia are in constant flux, meaning any single criterion for evaluation may quickly become obsolete. This is particularly true for the “green skills” and “wicked policy issues” of climate change and sustainable development, which require innovative, comprehensive solutions that can be modified in the light of experience and on-the-ground feedback.

Secondly, the problem is socially complex. Solving it requires coordinated action from a wide range of stakeholders, including government agencies, NGOs, private businesses, and individuals. This is not a problem for any one organisation to tackle alone. Environmental and socio-economic issues, for example, cannot be addressed by a single university or even a single government department. They require action at every level—from international to local—and the active involvement of the community.

Finally, the most challenging aspect is achieving sustained behavioural change. Solutions to most wicked problems, including the successful adoption of CBE, involve altering the behaviour and gaining the commitment of citizens, students, and educators. A disengaged and passive public can be a significant barrier to progress and is a factor in the policy failures around some of Africa’s long-standing problems. In areas like employment and education, considerable progress requires the active involvement and cooperation of all citizens. Given this complex landscape, what is the way forward for African universities? We must abandon the traditional, linear approach to problem-solving and embrace strategies that are as dynamic as the challenges themselves. Three of these are advanced in this Blog:

- Foster Collaboration and Engagement: A key conclusion from the literature on wicked problems is that effectively engaging the full range of stakeholders is crucial. Solving a wicked problem is a fundamentally social process. Universities must work across their institutional boundaries, with other jurisdictions and organisations, to create a shared understanding of the problem and a collective commitment to possible solutions. This is not about simply informing or consulting with citizens; it is about active participation where stakeholders can propose policy options and engage in debate.

- Adopt Holistic and Innovative Thinking: Linear thinking is inadequate for tackling the interactivity of causal factors and conflicting policy objectives that define wicked problems. We need to adopt a holistic perspective that encompasses the broader context, including the interrelationships between all causal factors and policy objectives. Universities, often characterised by vertical silos, must become more adaptive and flexible. This requires encouraging new, innovative ways of thinking and working, and actively supporting the innovators both inside and outside the institution.

- Redefine the Faculty Role: CBE necessitates a fundamental change in the role of faculty. Their role shifts from a “sage on the stage” to a “sage on the side”. Faculty members are no longer simply lecturers; they become guides, mentors, and facilitators who help students synthesise and apply knowledge at a pace that is right for them. This requires a new style of management for “learning organisations,” one that encourages initiative and recognises the need for continuous learning. In addition to the critical factors of collaboration, holistic thinking, and redefining the faculty role, two more crucial factors are necessary for advancing Competency-Based Education (CBE) in African universities:

- Sustainable Provision of Tools and Resources

The shift to CBE is not merely a pedagogical change; it requires a robust and sustainable technical infrastructure. Traditional classrooms and lecture-based instruction are fundamentally different from the learner-centred, technology-enabled environments required by CBE. African universities must be sustainably provided with the tools and resources needed to support this transition. This includes access to reliable internet connectivity, modern learning management systems (LMS), and digital tools for content creation and assessment. Furthermore, it is essential to equip educators with the necessary digital literacy and pedagogical skills to integrate technology into their teaching effectively. Without a consistent and strategic investment in these resources, the promises of CBE, such as personalised learning, flexible pathways, and continuous assessment, will remain out of reach. Ensuring this provision is sustainable requires strong partnerships with governments, international organisations, and the private sector, moving beyond ad-hoc projects to long-term, systemic support.

- Enhanced Policy and Technical Frameworks

For CBE to thrive, it must be supported by a coherent and comprehensive policy framework that aligns national educational goals with university-level implementation. Many African countries have adopted CBE at the basic education level, but this has not always translated into a clear framework for higher education. A robust policy framework should address critical aspects such as quality assurance, accreditation of CBE programmes, and the recognition of prior learning (RPL). It should also provide clear guidelines for curriculum development based on defined competencies and ensure that assessments are both valid and reliable. Furthermore, the technical framework must provide the tools and standards to facilitate the seamless integration of CBE. This includes establishing national or regional qualifications frameworks that link different levels of education and training, ensuring that competencies gained at one level are recognised and valued at the next. Without a supportive policy and technical ecosystem, universities will struggle to implement CBE consistently, and the benefits will be unevenly distributed across the continent.

These are not easy changes, but they are necessary. We must move beyond simply discussing these challenges and collectively chart a course toward a verifiable, impactful, and truly competence-based future for higher education in Africa. The upcoming RUFORUM Annual Meeting is more than just a conference; it is our vital platform for this very purpose.

This is our chance to move beyond the abstract and engage in intelligent, productive dialogue about the different interpretations of the problem and the collective intelligence needed to solve it. Let us come together to debate, share, and collaborate, not just as academics, but as partners in a collective journey to build a more empowered and skilled generation of African leaders. The time for action is now.

References

Bawa, A. & Boulton, G. (2024). Universities at the intersection of past, present and future. Transformation: Critical Perspectives on Southern Africa, (113), 100-130. doi:10.1353/trn.2024.a942969

Hulela, K., Mukuni, J., Abreh, M. K., Kasozi, J. A., & Kraybill, D. (2021). Transformative curricula and teaching practices to meet labour market needs in tertiary agricultural education in Africa. In Transforming tertiary agricultural education in Africa (pp. 126-134). Wallingford UK: CABI.

Patel, Z. (2025). Advancing just and sustainable urban transitions: strengthening the role(s) of African universities. Global Social Challenges Journal, 4, 46–62 https://doi.org/10.1332/27523349Y2024D000000032